Left: Julie Tolentino (born 1964), THE SKY REMAINS THE SAME: Tolentino Archives Ron Athey’s, Self-Obliteration #1, 2008. Chromogenic color print, edition 1 of 5, 17 × 11 inches. Documentation courtesy of Leon Mostovoy, Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Leon Mostovoy.

THE TRAVELING exhibition Art AIDS America at the Tacoma Art Museum is a feat of tenacity. In the 10 years that co-curators Rock Hushka and Dr. Jonathan D. Katz worked on the show, they tried to circulate the exhibition, and, as Katz notes in his catalog essay, almost 100 museums turned it down. This could be because of its unusual organization — as Hushka notes, “the art refuses any categorizing; usually it’s not chronological, there’s an intro wall, including a 10-minute video, to set the stage, and then the viewer moves into the show’s broader themes” — or it could be due to the exhibition’s dizzying array of materials, as well as their often strange and unsettling nature.

One hundred and three artists are represented, 23 of whom died of AIDS-related causes, while others are living as HIV positive. The 127 works in the exhibition utilize different media, procedures, materials, fabrications, ideologies, and intensities, and were created by art collectives and individual artists. Some works occupy the gallery or exist as projections, documented sites, or actions, or even depend upon the inclusion of the viewer’s shadow. Some of the work was made by individuals on their deathbeds or was commissioned from there. One Jerome Caja work, Bozo Fucks Death from 1994 — created with nail polish, enamel, and whiteout on a plastic tray — took five years to track down, a story that probably deserves its own miniseries.

The breadth of work included is organized into six thematic areas. One area, Memento Mori, includes works that acknowledge the precious and precarious nature of life through works that tell stories of love, rage, and loss. David Wojnarowicz’s mixed-media work, Untitled (Hujar Dead), from 1988–’89, incorporates a damning text that indicts the obscenities of contemporary life and the political realities that enabled a pandemic. His rant, collaged with photographs of the deceased artist Peter Hujar, includes passages such as: “I wake up every morning in this killing machine called America and I’m carrying this rage like a blood filled egg […].” Written in Sand (1992) is from Karen Finley: Memento Mori, the legendary performance artist’s 1992 exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. In that show, Finley addressed fragility and memory by using a chest filled with sand in which to write and then wipe away the names of loved ones, each a treasure lost. Many works in the show are called “Untitled” because, at the time they were made, federal funding for art with homosexual content or its exhibition was outlawed.

The Tacoma Art Museum backed up the exhibition with programs featuring conversation series, curator talks and walkthroughs, artist talks by Micha Cárdenas and Karen Finley, receptions, and a presentation by Julie Rhoad, the CEO of the NAMES Project Foundation, which produced the AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1987. Future scheduled events include a talk by members of the art collective Gran Fury; “Faith and Positivity,” an interfaith panel about pastoral care and support provided to those suffering from HIV/AIDS; and “Art Salon: A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Art AIDS America,” a panel on the intersection of art, AIDS, and psychoanalysis.

A preview exhibition of Art AIDS America took place at the 30th anniversary celebration of West Hollywood, a city established by activists, renters, and seniors in part due to government inaction surrounding the AIDS crisis. The dialogue in a recent docent training given by Hushka and the museum’s Director of Education, Samantha Hightower Kelly, anticipated viewers’ need for a reflective space in which to process the challenging works, “so that people feel comfortable where they’re at.” The exhibition deals with repression, pain, sexuality, death, isolation, and the viewer’s own emotional history, and thus requires space for viewers to process their reactions to the at times brutal imagery and evidence of staggering injustices.

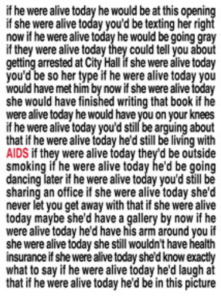

fierce pussy (formed New York, New York, 1991), For the Record, 2013. Two offset prints on newsprint, two panels, installed: 22 5⁄8 × 70 inches. Courtesy of the artists. Photo courtesy of the artists.

Art Collective Fierce Pussy contributed For the Record (2013), a textual montage that noted connections to the present day: “if he were alive today you would be arguing about that; if she were alive today you’d be texting her right now; if they were alive today they could tell you about getting arrested at City Hall.” An edited version of the piece is available as a takeaway broadsheet. A striking found object work by Daniel Goldstein, Icarian II, Incline (1993), consists of a shield of leather taken from a cast-off weight-lifting bench from a 1970s-era Castro Street gym and reclaimed as an uncanny index of physical language. The upper half of the surface is faded from the pressure of straining bodies, and sweat darkens the leather along the top and at the bottom.

Art Happens in Context: TAM AIDS Timeline

Art Happens in Context is the Tacoma Art Museum’s AIDS Timeline created by Samantha Kelly and the marketing team. The timeline format was used by the art collective Group Material (active 1979–’96) in Timeline: A Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America (1984) and AIDS Timeline (1986). Art Happens runs from 1981 to 2014 and marks events in blocks of color: art and pop-culture moments in lavender, political events in green, and medical milestones in light blue. Images from the exhibition are arrayed along the timeline, starting with Izhar Patkin’s Unveiling of a Modern Chastity (1981), a composition made with red-painted latex wounds laid into gastric-yellow rubber on canvas. At six-feet-by-four, the work is roughly human scale, an unnerving and sublime landscape of the Kaposi Sarcoma lesions invading the unsuspecting Patkin and his friends.

The first text in the timeline reads, “The CDC publishes the first report of young gay men with Pneumocystis Carinii Pneumonia (PCP) and Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) in LA,” and by 2008, “Seattle native Timothy Ray Brown, known as Berlin patient, is believed to be cured of HIV following two stem cell transplants. Brown remains free of HIV and cancer as of today.” There are two graph lines, one steadily rising register of HIV infections in the US up to the present and another noting the recorded deaths due to AIDS, which peaked in 1995 at 48,979, then began dropping when HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy, a.k.a. “AIDS cocktail”) changed the prognosis from terminal to medical maintenance. An epilogue notes that “1.2 million people in the US are living with HIV. Almost 1 in 8 are unaware of their infection.” HIV/AIDS is a contemporary concern and what has changed is the efficacy of the medications, which, by a CEO’s whim, can become financially unavailable overnight (in September 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals tried to raise the cost of Daraprim by over 5,000 percent, from $13.50 to $750).

Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID) was the first acronym assigned by the CDC on June 5, 1981, as it reported an unexpected cluster of cases, five gay men in Los Angeles who died of a rare form of pneumonia: Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). As the demographic shifted to include Haitians, hemophiliacs, and the female partners of those infected, what was known as GRID in 1981 became AIDS in 1982. The disease stymied the political progress of LGBQT communities: Dr. Katz notes the impact in a footnote in his catalog essay “How AIDS Changed American Art”: “AIDS pushed the social and political agenda of the queer movement back several decades, and we are only now beginning to undo some of the political damage AIDS carried in its wake.” Many have noted that AIDS also galvanized and politicized a generation, and one wonders whether the support for and eventual legal success of gay marriage would have come any sooner if AIDS hadn’t happened.

The Culture Wars, AIDS, and Censorship

In the spring of 1989, the American Family Association and its right-wing leader, Rev. Donald Wildmon, led a grassroots letter-writing campaign against an exhibition that included an Andres Serrano photograph, Piss Christ (1989). On May 18, 1989, Senator Alfonse D’Amato denounced Serrano’s work and was joined by Senator Jesse Helms, who called the piece “blasphemy.” Along with 20 other senators, they went on to draft a letter to Hugh Southern, then acting Chair of the NEA, demanding to know “what changes the agency would make to its grant procedures.” A juried panel of the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA), indirectly a recipient of NEA funds, had chosen Serrano and nine other artists for $15,000 fellowships and the three-city touring exhibition, Awards in the Visual Arts 7, that had so incensed Reverend Wilmon and the AFA.

Also at this time, the retrospective Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment, which had been well-received in Philadelphia and Chicago and was scheduled to open July 1, 1989 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, was targeted by Representative Dick Armey, who sent a letter to Southern signed by 100 congressmen denouncing Serrano and Mapplethorpe, threatening to cut the NEA budget, and insisting on changes to grant guidelines. Eventually Corcoran Director Christina Orr-Cahall canceled the show. The exhibition went to an alternative local space, the Washington Project for the Arts, and then on to the Cincinnati Museum of Contemporary Art, where that venue’s director, Dennis Barrie, was charged with obscenity. After listening to five days of testimony involving several museum directors, a mostly working-class jury took two hours to acquit Barrie.

As Carol S. Vance noted in a 1990 Art in America piece entitled “The War on Culture,” “the Right long recognized [that] the arena of representation is a real ground for struggle.” In July 1990, Senator Helms introduced an amendment that made it impossible for museums to receive government support if an exhibition included offensive, indecent, or otherwise controversial art. The censorship of art for unconventional — specifically sexual and, more precisely, homoerotic — imagery was linked to the politics surrounding the AIDS pandemic, which generated plenty of fear for demagogues to peddle.

Stratagem(s)

Dealing with these political complications became a topic of the works themselves, as artists developed new tactics to smuggle unconventional or controversial content into their works. As noted above, some artists named pieces Untitled, with perhaps an accompanying phrase inside parentheses that revealed clues about the artists’ associations and intentions. Roland Barthes’s 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” with its postulation that control of textual meaning resides with the reader not the creator, provided something of an alibi for hot-button content. By ascribing artistic meaning to the viewer’s thought processes and not the artist’s explicit intentions, museums could display works by gay artists without fear of being censored under the new laws. Felix Gonzalez-Torres noted in a 1994 interview with Robert Storr that a homophobic senator who threatened to show up at the Hirshhorn opening of his exhibition would “have a really hard time explaining to his constituency how pornographic and homoerotic two clocks side-by-side are.”

Poetic Postmodernism

Co-curator Katz coined the term “Poetic Postmodernism” to cover significant territory in this exhibition. Artists in this category include Andres Serrano, Robert Blanchon, Ray Navarro, and Kiki Smith. In his catalog essay, Katz, Director of the Visual Studies Program at the University of Buffalo, notes that “new communicative situations are born all the time in the art world,” such as the viral techniques of the Cuban-born artist Gonzalez-Torres, who said, “I want to be invisible, infiltrate, [and] once you’re inside try to have an effect. The enemy is too easy to dismiss or attack …” Kiki Smith’s Red Spill (1996), a memorial to the artist’s sister who died of AIDS in 1988, can’t escape its source: the blown-glass forms, in the shapes of red blood cells, are arrayed on the floor rather than on some kind of support, each piece (and the spaces between them) conveying the artist’s mastery of visual shapes and effective, heartfelt form.

Gonzalez-Torres felt that all cultural production is political and noted that the most effective ideological constructions are the ones that disguise their overt intentions. His finely calibrated works resist specific or singular meanings: "Untitled" (Perfect Lovers), from 1987–’90, includes two ordinary clocks installed next to each other. Using mass-produced items and commodities that can be endlessly replenished, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation allows numerous “manifestations” of his works, as he did when alive, with pieces recreated at the same time in different venues. The implications of his iconic candy-pour pieces — installations of piles of shiny wrapped candies that viewers can pick up and eat — may be related to the number of T-cells a healthy body has or to the ideal weight of his partner, Ross Laycock, who passed away from AIDS in 1991. "Untitled" (Still Life), from 1989, is made from small blue pieces of paper that viewers can take, each featuring ambiguous words and dates from the artist’s life, like a timeline piece crossed with viral dissemination.

Let the Record Show, Gran Fury, and ACT UP

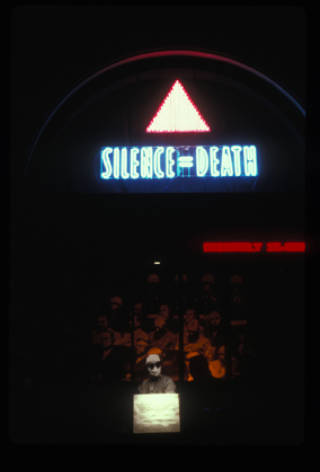

Gran Fury’s Let the Record Show (1987) is recreated in the exhibition as a projection and placed within the Grassroots Activism, Political Art, Activist Art category. Both Let the Record Show and the art collective Gran Fury developed via the movement ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. In November 1987, the curator at the New Museum, William Olander, attended an ACT UP meeting and offered the use of the museum’s window on Broadway in Soho for a project that would be a demonstration in visual terms. Gran Fury member Marlene McCarty observed that, “each time we gathered to work on the window, a different constellation of people showed up. It wasn’t until later that we decided to form a collective.” Another Gran Fury member, Tom Kalin, noted that AIDS definitely politicized a generation and pointed out that at that time people didn’t have cell phones, Facebook, or email: “People went on the streets, and the streets were full of all sorts of information and imagery.”

ACT UP NY/Gran Fury (active New York, New York, 1987–1995), Let the Record Show..., 1987/recreated 2015. Mixed media installation, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gran Fury and the New Museum, New York. Photo courtesy of the artists.

Let the Record Show featured elements, tactics, and artists from the 1986 Silence = Death Project, an installation with a neon sign flashing SILENCE = DEATH accompanied by a pink triangle. This visual code used by the Nazis to indicate a homosexual, now invested with empathy, fervor, and pride, was stationed in front of a backdrop image of the Nuremberg trials and above photographs of such figures as Rev. Jerry Falwell, Cardinal John O’Connor, and Senator Jesse Helms, with egregiously ignorant and homophobic comments by each cast in concrete. President Ronald Reagan’s slab holds quotation marks but no quote, since Reagan made no mention of AIDS until he answered a question asked by a reporter at a September 17, 1985 press conference. He made his first major address on the topic on May 31, 1987, at the Third International Conference on AIDS in Washington DC. By that time 36,000 people had been diagnosed and over 20,000 had died.

Jonathan Horowitz’s piece, Archival Iris Print of an Image Downloaded from the Internet with Two Copies of the New York Post Rotting in Their Frames (2004), is a found image on archival paper of a person who has just died of AIDS. Framed with it are two front pages of the New York Post from June 2004, one featuring an image of the former President Reagan (who had just died) and another of his wife, Nancy. Horowitz elicits his own justice in a form that depicts an inversion of power relations, wherein the portraits of the powerful couple, printed on cheap, disposable paper stock (you can practically hear the hissing of the acid in the pulp newsprint) are entwined with the image of the anonymous young man, which is destined to outlast them both.

Artworks with homosexual and AIDS-related content are still viewed throughout the art world as something of a “third rail,” with exhibitions, artists, and works still restricted in terms of funding and venues. Katz weathered the removal, by Republican politicians, of the David Wojnarowicz film A Fire in My Belly (1986–’87) from Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, the show he curated at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, in 2010 — and which the Tacoma Art Museum showed in 2012. The exhibition checklist for Art AIDS America demonstrates that most of the artworks were lent by galleries and private collections, with just a few coming from other museums. Katz praised the TAM as a museum with the potential to advance museology past its conservative agenda. Carol S. Vance stated, “If we are always afraid to offer a public defense of sexual images, then even in our rebuttal we have granted the right wing its most basic premise: sexuality is shameful and discrediting.”

The Jerome Project is an art-historical effort mounted by filmmaker Anthony Cianciolo to preserve and further the artistic legacy of the late artist and performer Jerome Caja (1958–’95). The aforementioned Bozo Fucks Death as well as Shroud of Curad and Little Yellow Angels are small, smart, mixed-media works featuring nail polish and eyeliner “that whirled together religion, art history and sinister sex,” painted onto surfaces the size of a tip tray (some actually were on tip trays). Caja’s work comes to this exhibition after, in some cases, years-long searches, representative of both the iconoclastic nature of the artist himself and the attrition of complicated, challenging works left to the vagaries of chance and the precarious financial state many artists live (and die) in. To this day, the NEA doesn’t fund individual artist grants in the visual arts.

Joey Terrill (born 1955), Still Life with Forget-Me-Nots and One Week’s Dose of Truvada, 2012. Mixed media on canvas, 36 × 48 inches. Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, Foundation purchase. Photo courtesy of Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art.

Deborah Kass (born 1952), Still Here, 2007. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 45 × 63 inches. Private collection, © 2015 Deborah Kass / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Legacy: Pro-Logue/Epilogue

Art AIDS America is an exceptional exhibition that brings together stunning works tethered in a variety of ways to the epic and ongoing crisis of AIDS. The category Legacy allows for a kind of debriefing, honoring memory and experience and creating a sense of hope: site determines the dimensions of the hanging beaded installation Untitled (Water), from 1995, by Gonzalez-Torres, which completely fills the space of a throughway and hangs perfectly, swinging freely and embracing those who walk through it. As the curtain moves, the shimmering aqua-and-clear beads evoke the reflection and color of the wind-ruffled water at a Miami Beach. Joey Terrill’s mixed-media painting Still Life with Forget-Me-Nots and One Week’s Dose of Truvada (2012) employs the art-historical tradition of the still life in terms of a political/private montage that includes his Mexican-American heritage and his current status as an HIV+ survivor, dependent upon life-sustaining medications that come freighted with side effects, lack of access, and inflated costs. Still Here (2007), from Deborah Kass’s painting series Feel Good Paintings For Feel Bad Times, is an oil-on-canvas work that appropriates a lyric from the Stephen Sondheim musical Follies: “… good times and bum times, I’ve seen them all / and my dear, I’m still here …” These simple words function as an anthem of endurance, as does the exhibition itself.

¤

Art, AIDS, America is on view at the Tacoma Art Museum, October 3, 2015 to January 10, 2016

¤

Elizabeth Pence is an artist and writer who lives in the Pacific Northwest. She has written articles and reviews for Artweek, Coagula Art Journal, and Angeleno Magazine.

LARB Contributor

Elizabeth Pence is an artist and writer who lives in the Pacific Northwest. She has written articles and reviews for Artweek, Coagula Art Journal, and Angeleno Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Still Radical 25 Years On

The shock we experience reading Karen Finley’s "Shock Treatment" is, ironically enough, less than the shock its narrator is forced to endure.

AIDS Without Its Metaphors

Dale Peck’s postmodern AIDS memoir revisits the gay early ’90s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F12%2F7-inch-tolentino_right-side_web.jpg)