Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna by Billy Wilder

Wilder cut his teeth as a journalist in Europe before moving to the United States, but his pre-Hollywood writing has long been unavailable to anyone not fluent in German. Wilder’s sharp and witty journalism is now available for English-speaking audiences in Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna. The collection has been edited by the great film historian Noah Isenberg and translated by the brilliant Shelley Frisch. Wilder’s writings in this compilation include work published between September 1925 and November 1930, from a range of newspapers he worked for prior to leaving Europe.

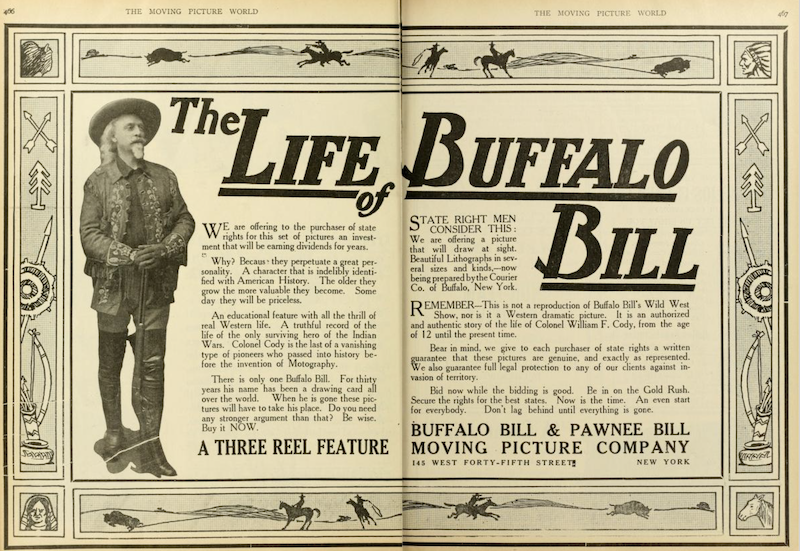

Isenberg sets up the collection by exploring the Wilder family’s early years. Billy Wilder was born in 1906 near Kraków, Poland, as Samuel Wilder. The name came from his grandfather, but his mother, Eugenia, preferred the name Billie. After all, Billy’s brother Wilhelm was already nicknamed Willie, so Billie and Willie had a nice ring to it. In addition, Eugenia had memories of traveling as a young girl to New York City, where she saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. She always loved the nickname, which seemed foreign and exotic to her. (Wilder is credited as Billie in this collection but I will refer to him as Billy to avoid confusion.)

Billy’s father, Max, ran a chain of restaurants along the Vienna-to-Lemberg railway line. The family moved to Vienna, “where assimilated Jews of their ilk could better pursue their dreams of upward mobility.” After World War I, the Wilders tried to get Austrian citizenship, to no avail, and they would remain “subjects of Poland.” During this time, Billy went to school across the street from a hotel popular for its hourly rates. Channeling his creative mind, Billy would dream up humorous tales about the patrons revolving in and out of the seedy establishment. After school, Billy discovered his love of film when he began to “spend long hours in the dark catching matinees at the Urania, the Rotenturm Kino, and other cherished Viennese movie houses.” While his father wanted him to pursue law, Billy was drawn to popular culture and journalism.

By the end of 1924, Billy found the courage to write to the local newspaper, Die Bühne. The aspiring writer offered to serve as a foreign correspondent, hoping it would be his crack at a trip to the United States. The only problem was that he didn’t speak English. Billy continued to visit the office and, with his “outsize gift of gab,” eventually talked his way into a post. One story Billy fondly told involved him walking in on the paper’s theater critic having sex with his secretary. He was quickly offered a promotion to stay quiet. In what sounds like something out of one of Wilder’s films, Billy was soon chatting with major talent such as actor Peter Lorre, then known as László Löwenstein. Between strokes of luck and aided by his native wit, Wilder became a real journalist, writing crossword puzzles, small features, film and theater reviews, and other popular profiles.

Wilder also got his first taste of fear as a journalist when Die Stunde’s prominent writer Hugo Bettauer (best known for the 1922 novel The City Without Jews) was shot dead by a “proto-Nazi thug.” Wilder never had an issue speaking truth to power, nor did he fear the political ramifications of his writing. Such thick skin served him well when he hammered Hollywood with Sunset Boulevard, a film that exposes the industry’s careless attitude toward its aging stars and struggling writers. In Cameron Crowe’s excellent 1999 book Conversations with Wilder, the director told a story of the first Hollywood screening of the classic noir film, when MGM studio chief Louis B. Mayer was heard kvetching to notorious fixer Eddie Mannix and executive Joe Cohen, “That Wilder! He bites the hand that feeds him.” When Wilder overheard the comment, he introduced himself and said, “[W]hy don’t you go fuck yourself.”

Looking back at his years chasing ledes, Wilder said that he was “brash, bursting with assertiveness, had a talent for exaggeration, and was convinced that in the shortest span of time [he]’d learn to ask shameless questions without restraint.” Anyone familiar with Wilder’s work in Hollywood knows that these skills served him well behind the typewriter and in the director’s chair. One assignment Wilder got as a budding reporter was to interview bandleader Paul Whiteman, who responded to Wilder’s enthusiasm by paying for him to travel with the band. Wilder composed his article from Germany, where he saw the band premiere Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” and then joined a new paper in Berlin.

Wilder’s profile of Whiteman gives us a glimpse into the future filmmaker’s eye for detail and his ability to channel humor through the seemingly mundane. For example, it was not Whiteman’s music that Wilder found most compelling; it was the composer’s mustache. According to Wilder, “If you add these things together — the most amusing mustache you could imagine, a truly charming little double chin, two gentle, childlike eyes in a nice broad face, a burly, graceful, tall man, dressed casually and unobtrusively — you get Paul Whiteman.” Wilder also learned that Whiteman was the United States’s second most popular celebrity, according to the Chicago Tribune, behind Charlie Chaplin and ahead of Jack Dempsey. Wilder continues:

There’s that mustache of his again, a splendid, peerless, divine, superb mustache. It alone would have made Paul famous, without a doubt. It is cut quite short and twirled up in the middle, the two ends extend out quite far, and it points upward toward his nostrils at a sharp angle; the tips have a bit of pomade, which adds an aromatic element to our visual pleasure. That is the mustache of the future. Copyright by Paul Whiteman.

If anyone could make a facial fashion statement the backbone of a print profile of a world-famous composer, it was Billy Wilder.

Wilder’s affinity for the United States burgeoned while he was in Berlin. He even served as a tour guide for Hollywood director Allan Dwan, who was in Germany for his honeymoon. As Isenberg notes,

Berlin in the mid-1920s had a certain New World waft to it. A cresting wave of Amerikanismus — a seemingly bottomless love of dancing the Charleston, of cocktail bars and race cars, and a world-renowned nightlife that glimmered amid a sea of neon advertisements — had swept across the city and pervaded its urban air.

It was in this climate that Wilder was able to fully embrace his love of popular culture and, most specifically, his admiration for American movies.

In Berlin, Wilder worked under the mentorship of Egon Erwin Kisch, whose reporting Wilder described as being “built like a good movie script. It was classically organized in three acts and was never boring for the reader.” Wilder also landed a job at Tempo, a tabloid perfectly suited for his cultural curiosities and acerbic wit, where he would begin writing about cinema. After introducing readers to Filmstudio 1929, an independent film company, Wilder eventually wrote a screenplay for a 1929 film, Der Teufelsreporter (A Hell of a Reporter), a blend of autobiography and hyperbole that, as Isenberg observes, served as an excellent primer for the journalists in Wilder’s future films.

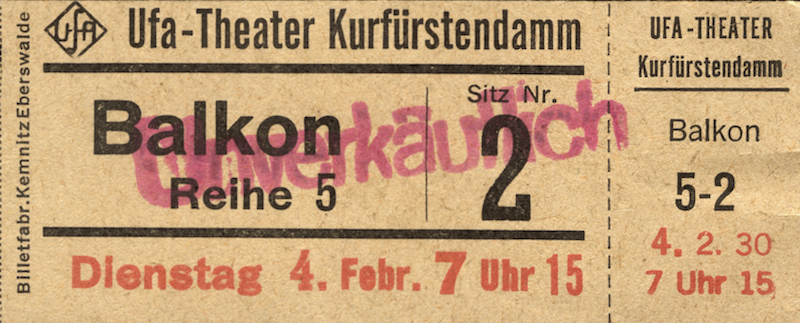

In his essay “How We Shot Our Studio Film,” Wilder chronicles the journey to complete a film without money or studio support. People on Sunday (1930) was a collaboration between Moriz Seeler, Eugen Schüfftan, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, and Wilder. The film began as scattered notes scribbled on coffeehouse napkins; the group had an idea and a camera, but that was it. Yet they managed to finish a screenplay, focusing all of their feelings about Berlin on the events of a single Sunday, and pitched it to an investor. Wilder writes that “three percent of [the investor’s] motivation was his belief in our abilities; 97 percent came from his interest in getting his hands on an incredibly cheap film.” Between weather problems and actors quitting, the men managed to complete the movie. Distribution was another hurdle; after they screened the film at a major studio, “[t]he head of the company tells us that after thirty years in the business he’d be willing to give up his job if this film ever somehow makes it as far as a showing, not to mention a success.” People on Sunday was eventually screened at UFA and would premiere at the U. T. Kurfürstendamm. One wonders if Wilder ever followed up with the executive willing to quit his job if the film saw the light of day.

Wilder also interviewed American billionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr. and couldn’t help but notice his subject’s crooked teeth. Speaking of himself in the third person, Wilder writes, “Why doesn’t he go to the dentist? The interviewer wonders. He finally gets the answer half an hour later: Mr. Vanderbilt has no time for dentists; he has to work, work hard and always.” Throughout their conversation, Wilder also gave Vanderbilt a fun ultimatum — did he prefer Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton? — and he picked Chaplin. Continuing his knack for seeking out intriguing subjects, Wilder also found himself interviewing a woman who openly practiced witchcraft. His curiosity and awe shine through every sentence. Wilder’s takeaway: “I think it’s worth noting, for cultural and historical reasons, that a witch was able to establish herself in 1927 and do well enough in her profession to live more than comfortably. Her clothing was definitely from a top-notch boutique.” Profiles such as these offer colorful examples of Wilder’s skills at observation and his penchant for the uncanny.

By 1929, Austrian director Erich von Stroheim had become a scourge to the Hollywood studio system, and Wilder knew it. Most famously, Stroheim’s first cut of Greed (1924) ran nearly nine hours; finding a print of the lengthy first cut has been an archivist’s dream for nearly a century. In a profile of the director he wrote in 1929, entitled “Stroheim, the Man We Love to Hate,” Wilder mused that “every child in Hollywood knows who ‘Von’ is,” though they pronounced it like “one” — the reason being that “every company can shoot only one film with him, then it goes broke.” Beneath von Stroheim’s megalomaniacal methods was a talented director who impressed many who worked with him. Wilder reports that von Stroheim’s convention-shattering work was steps beyond other major filmmakers. He also notes that von Stroheim was dismissed from the film Queen Kelly (1929), starring Gloria Swanson, when he refused to film sound inserts as the studio demanded (since the industry was transitioning away from silent films). As fate would have it, Wilder himself would pair von Stroheim and Swanson again in Sunset Boulevard, and scenes from Queen Kelly are seen in that movie when Swanson’s character, Norma Desmond, screens them for down-on-his-luck writer Joe Gillis (played by William Holden).

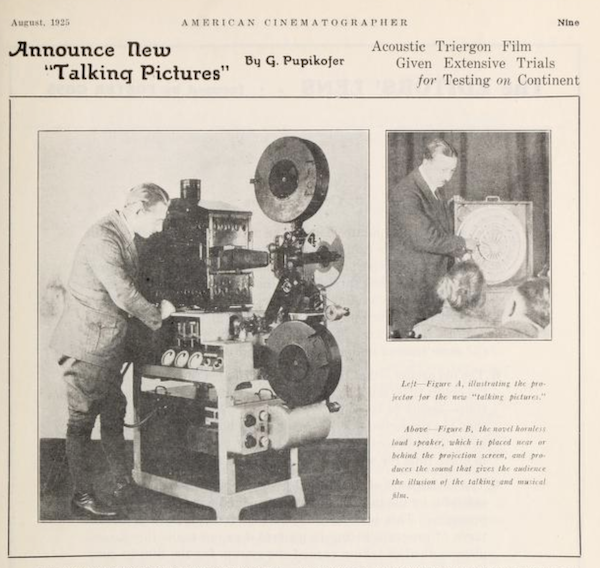

In another essay, Wilder details a day he spent at a German film studio. The director was filming with the Tri-Ergon system, a sound-on-film application similar to what would eventually take over from the sound-on-disk system then prevalent in Hollywood. Wilder writes as someone interested in and optimistic about the advent of sound film. The studio’s attention to detail and concerns about avoiding unnecessary noise were evident when Wilder arrived to find that he couldn’t get in because the set was locked down: “Imagine you’ve been invited to be a guest at a house and you show up on time but find the doors locked.” He was there to watch Max Mack shoot Ein Tag Film (A Day in Film [1928]), which revolves around an actress’s struggles on a film set. In this absorbing piece, Wilder is deeply curious about the significance of movies transitioning to talkies, and clearly in full command of the various implications.

The selections in Billy Wilder on Assignment show Wilder carefully honing his skills at splashy prose and erudite analysis. Reading these essays gives us a better understanding of the filmmaker’s first profession, which served him so well in Hollywood. The book concludes during the time Wilder was involved with Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday), by which point he had used the career he’d cultivated in journalism to begin working actively on films. Times were not always great, however, as Wilder would soon transition from being a screenwriter at UFA to a refugee in Paris, after the Nazis rose to power in Germany. Eventually he came to the United States on a British ocean liner in January 1934, with $20 in his pocket and a minimal command of English.

Billy Wilder on Assignment is full of glorious turns of phrase, entertaining narratives, and quirky characters. Shelley Frisch, this book’s superb translator, observes that “Wilder’s prose is, well … wilder than I usually get to render in my translations.” She continues, “Where else do I get to write about ‘witless wastrels,’ about an Englishman ‘blessed with hearing like a congested walrus,’ about a performer with ‘gasometer lungs,’ or a smoker who can ‘make his pipe saunter from one corner of his mouth to the other’?” Frisch is a serious Wilder fan who safely assumes that we all love Some Like It Hot.

Thumbing through Wilder’s essays from the 1920s will make you feel as if you are enjoying yourself at a German coffeehouse, catching up on popular culture, and planning your next weekend adventure in the Weimar Republic. Isenberg and Frisch have done a great service for film historians and fans of classic Hollywood. There are very few filmmakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age whose formative years are worthy of such a deep exploration. With Billy Wilder on Assignment, we get to take a fascinating and entertaining journey with the best narrator of his day.

¤

Chris Yogerst is associate professor of communication in the Department of Arts and Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His new book is Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into Warmongering in Motion Pictures (University Press of Mississippi, 2020).

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Man and His Persona: On “Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise”

A revealing biography of an iconic Hollywood star.

“Here Lies Herm — I Mean, Joe”: On Sydney Ladensohn Stern’s “The Brothers Mankiewicz”

Alex Harvey delves into “The Brothers Mankiewicz” by Sydney Ladensohn Stern.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F04%2Fbillywilderonassignment.jpeg)