Maya Deren: Choreographed for Camera by Mark Alice Durant

“Elinka [Maya Deren’s pet name, adapted from her birth name, Eleonora], do you remember being lost in the snow?”

“Yes, Momchka.”

“On the Polish border, you were five years old, at night, lost in the snow, I called and called but I had to whisper because we were escaping.”

“Yes.”

[…]

Long minutes passed in silence, Deren called out, “Momchka, save me.”

“Yes, I will, Elinka.”

“I know you will, Momchka.”

We assume that the dialogue is factual, substantiated in a record, a letter, a journal. But then, the author performs a near-miraculous feat. He writes from within Maya Deren’s unconscious as she lay motionless in Saint Albans Naval Hospital in Queens:

Maya held onto her mother’s voice as long as she could. She felt herself blinking in and out of the hospital room, the dim fluorescent light above her bed, the window black with night weakly reflected her mother’s figure, the warmth of her mother’s hand. […] She walks with a cat over her shoulder, she recognizes that it is Ghede. […] The light is bright but diffused, it seems to come from all directions.

In the early hours of Friday, October 13, Deren experienced a second hemorrhage, fell into a coma, and never awoke. Though there can be no quibbling about the finitude of this event, Durant manages, through his immersive, speculative prose, to introduce to his readers the notion of spatiotemporal dislocation that characterizes Deren’s mythical, noirish cinema.

In his afterword, Durant — who writes about photography for Art in America, Aperture, Foam, and Photograph, among others — outlines his repeated frustrations, loss of nerve, and eventual reclamation of the biographical project: “I freed myself from the burden of writing the definitive chronicle of Deren’s life, and instead composed my version, based on research and scholarship, but open to the imaginative.”

The “imaginative” element in Maya Deren: Choreographed for Camera furnishes some of the book’s most compelling passages. A consequence of his version, however — a transgression of traditional biography — is that the author’s burden (accurate reportage) becomes the reader’s burden (assessment of veracity). At times, this obligatory inheritance is muddying, but for the most part, it isn’t a problem. Deren’s films contain so much slumbering anoesis that you wonder by what miracle a mortal biographer managed to straighten any of it out at all. Deren’s legendary status as one of the most daring filmmakers and elusive minds of the 20th-century avant-garde prevails — who wouldn’t want to crawl inside?

¤

The arc of the story is this: a woman seeks to inhabit the world of the living and the dead. Her conviction is ravenous; her temperament volatile in the way that cool, clear liquid can ignite a lethal fire. Though she makes indelible contributions to her field, sustained mainstream recognition eludes her. After a streak of successes, she evaporates into a cloud of esoterica, sliding in and out of visibility in the decades succeeding her death.

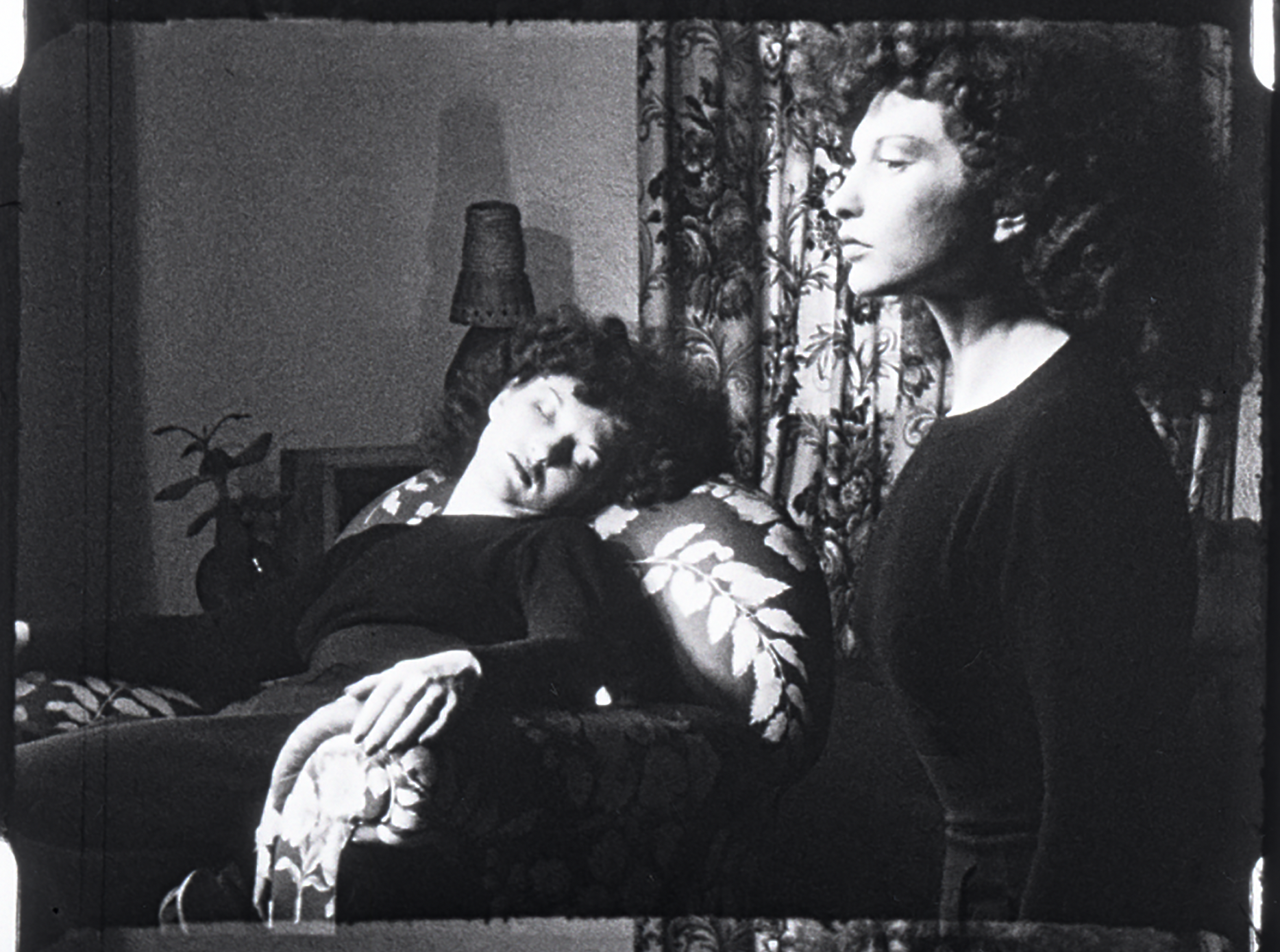

Mark Alice Durant excavates her determined life with grace, elevating tidbits of common knowledge (Deren’s fondness for cats, for example, which I happen to share), while underscoring her singular accomplishments in the realm of art, theory, and film. He begins his account, fittingly, with a generous sequence of images that are as spectacular as they are beguiling, showcasing, in grainy monochrome, iconic frames from Deren’s major works. Bodies writhe as though underwater; shadows warp from distorted perspectives; sculpted figures, coiled in serpentine pose, bear down their vertiginous gaze. The last of these images, a still from Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, provides what is arguably the most famous portrait of Deren, and certainly the most enduring. Durant describes the scene, which was filmed in the spring of 1943 at the home Deren rented in Los Angeles with her collaborator and husband, Alexander “Sasha” Hammid:

She is sealed behind glass. Her fingertips press lightly on the transparent surface as if to confirm the barrier between the interior and the exterior. The window is a medium of dueling functions — reflecting and transmitting. She looks out at the world full of things and people, but is aware of herself as an image, as the camera sees her.

Durant does this quite a bit, writing through Deren’s hallucinatory images to conjure them on the page. The translation is necessarily imperfect: an overdub of dubious merit. Still, the reader emerges with an impression of Deren’s dreamlike, enigmatic complexity. Her incorporation of theatrical and choreographic gesture and her interest in duplicitous subjectivity, ritual, transfiguration, and ethnography produce in her films a unique experimental quality that is neither purely formal nor wholly poetic. Her cinema is one of poetic realism. Though she was resolutely anti-Hollywood, rejecting outright its commercial conventions, she retained an affinity for classicist filmmaking principles. Because of these uncommon overlaps, her work is frequently described as a linchpin between the European avant-garde cinema of the 1920s and ’30s and the American experimental film that followed. Her legacy, beyond a mesmerizing array of film works, is in her relentless crusade to establish personal, independent filmmaking as a legitimate art form.

Choreographed for Camera is composed of more than 50 discrete chapters (one could even call them “movements”), sequenced chronologically, but which vary in tone and authorial approach. Some isolate a particular event or period; others orient entirely around a person of note in Deren’s life. (See, for example, the chapter on Katherine Dunham, or the chapter on Alex Hammid.) Durant admits that, in an early attempt to structure his book, he considered a nonlinear ordering of disparate scenes from Deren’s life, in a manner that emulated Deren’s experimental editing technique, “with the hope of upending chronological expectations.” Perhaps for this reason, a sense of distinctness between chapters abounds, though as a whole, they deliver the story of a brilliant, sometimes difficult, always defiant woman who galvanized a new movement in American cinema.

The first chapter opens with an image — a heavily patinated photograph of a child decked out in a chinchilla-trimmed velvet coat, replete with fur muff. The photo was taken in Deren’s birth town of Kyiv in 1921, when she was four years old and her name was Eleonora Derenkowska. One year later, she and her Russian Jewish parents, fleeing a series of antisemitic pogroms in Ukraine, emigrated to the United States. Her parents were well educated, and in the US, their elite cultural status remained largely intact. Deren’s father, a psychiatric physician, was employed by the Syracuse State School for Mental Defectives. Marie, her mother, was a conservatory-trained pianist who traveled often on her own. In 1928, when they became naturalized citizens, the family name was shortened to “Deren.”

Durant curtly introduces the nuclear family and sets up the dynamic of desire and distance between cosmopolitan mother and endearingly precocious daughter. To address her mother’s frequent absences, the young Eleonora penned letters. Durant presents several of them in full, providing the reader insight into her witty, unselfconscious, and often whimsical observations. Reading around the whimsy, any adult reader will intuit just how desperate Deren was to engage her mom in reciprocal conversation (“Dear Mama, Have you gotten my long letter yet? Why didn’t you write?”) To coax a response, she hedges, “If you ask questions it is easier for me to write letters.” Durant’s curation is astute; he quietly assembles an outline of a wily, intuitive child, withholding his own authorial commentary so that Deren might speak for herself. (She seems to have earned the right, even at 10 years old.) Her letters expose the force of her imaginative capabilities, and she writes fluidly of altered perceptions in dream states, the emotional depth of animals, the strangeness of mirrors, and the confounding power of doubles. She writes of a dream in which she is transformed into a Christmas ornament shaped as a doll and abused by the child who was her “careless mother.” The tone of her unencumbered epistles calls to mind the narrator in Unica Zürn’s Dark Spring, ironic given the lengths Deren would later go to defend her work against the label of surrealism.

Choreographed for Camera further brims with insights into Deren’s early political and ideological awakening, a crucial background against which to read her later theoretical formations. By the time Deren was 13, she and her mother had returned temporarily to Europe so that Deren could attend Geneva’s prestigious International School. (Meanwhile, Marie would study French at the Sorbonne.) Though the parallel is not made explicit, Durant allows us to see how a spirit of self-determination and intellectual rigor invigorates them both. Waiting for Mahatma Gandhi to appear at a lecture hall in Geneva, she tuned in to the trance-like dimension of collective expectation. “The silence of waiting and anticipation was the most reverent and awesome experience I have ever had,” she writes. Like the beat before a scream, “It was the perfect experience of silence.”

As an undergraduate at Syracuse University, where she studied journalism and political science, Deren joined the staff at the student-run Syracuse Daily Orange and signed on to student activist clubs, including the hashtag-ready “Social Problems Club,” and the Young People’s Socialist League. As a trilingual immigrant from Kyiv, she was concerned with rising fascism in Europe and the civil rights abuses occurring in the States. At the same time, one senses that her involvement in radical activism was at least partially fueled by a desire to associate with people as voraciously determined, as incendiary, as she considered herself to be. “He is a very big shot in the radical movement,” she boasts in a letter to a friend about her first college lover, whom she would swiftly marry and divorce.

From early on, Deren hungers to trespass where barbed-wire fences cordon the juiciest forbiddens. This is the feeling that surfaces inside every teenage girl at some point. The question of what to do with it — smother it, denounce it, or go running madly across the field — is what distinguishes us. Deren embraced the latter. She ponders in a letter to a friend about an oversized gold bracelet she elects to wear as an armband above the elbow: “Something of the mad paganism of it, the wild gesture of barbarism, the rejection of convention that it symbolizes, fascinates me. […] Inside I am quite mad, emotional and sometimes, in little things, I am what I really am.”

Sometimes, I am what I really am. “A little thing,” she continues,

like laying in the shadows of the lilac bush. Have you ever done it? Lain with your hair in the mud, and the cool torrent beating pounding relentlessly and ruthlessly on your naked body, pressing it into the earth from whence it sprang, blinding your eyes, choking you, taking you for its own, and then watching the lull, the end, the moon climbing up the tear-cleared skies, creeping stealthily inside, a glorious sin in your heart?

¤

After completing her MA in English literature at Smith College in 1939, Deren wrote to Katherine Dunham — the legendary dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist at the forefront of American and Black modern dance — in the hopes of being hired with the Dunham Company. Dunham was revered for her innovative interpretations of Caribbean dance, traditional ballet, African rituals, and movements and rhythms of the African diaspora to create the Dunham Technique, an anchor in what is now referred to as the field of Ethnochoreology. Deren’s letters went unanswered, so she staged an intervention. “My recollection of Maya (Eleanora),” recounts Dunham in the book, “is of her walking into my dressing room, after several attempts at appointments, and convincing me that I needed a secretary to travel who knew dance.” The hands-on approach worked and Deren landed a job, after which she tried more than once to initiate a creative collaboration with Dunham, who consistently ignored her advances. Though a sanctioned collaboration never got off the ground, Durant notes that Dunham was the gateway to the major concerns that would inform Deren’s career:

In Dunham’s employ, Deren had access to the field notes and films that Dunham had made in the Caribbean, and was privy to her plans for her book on Haiti, Island Possessed. Deren took a fervent interest in the Haitian material, particularly the phenomenon of spirit possession in Vodou.

It was likewise through Dunham and her social cadre that Deren was introduced to her first collaborator and future husband, and turned to film as a principal medium.

In 1946, after independently distributing her films to colleges and libraries, 26-year-old Deren published An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, her first major critical statement on filmmaking. The ambitious essay defines the terms of her practice and crystallizes the nascent movement of New American Cinema that would dominate the latter half of the 20th century. That same year, she was awarded the first Guggenheim Fellowship for filmmaking and, with the grant’s financial support, arranged a trip to Port-au-Prince. Regarding her trips to Haiti, Durant devotes multiple, fascinating chapters, engaging with the racialized dimension of Deren’s ambitions. He explains that, “[b]ecause of her somewhat unruly hair and ‘exotic’ features, when traveling [in the United States] with the all black Dunham Company, Deren was often assumed to be black or mixed race by the white people she interacted with.” After a day of filming with Deren, Anaīs Nin also wrote in her diary of Deren’s “fascinating face”: “She was a Russian Jewess. Under the wealth of curly, wild hair, which she allowed to frame her face like a halo, she had pale blue eyes, and a primitive face. The mouth was wide and fleshy, the nose with a touch of South Sea-islander fullness.” (She made mention, too, of Deren’s assertive and sensuous “peasant body.”)

Durant and his book’s interlocutors make frequent mention of Deren’s “wild” or “unruly” hair tinted red with henna, the implication being that her appearance was coordinated in defiance of white feminine bourgeois ideals of the time. When she adopted the name “Maya” and sewed her own Russian-folkloric-inspired clothing, Deren seemed to be willfully coding her femininity as an interplay of sensuality and power, curating an inflection of “exoticism” — a particular mode of aesthetic perception that, according to postcolonial scholars like Graham Huggan, renders things strange even as it domesticates them. (The iconic portrait of Deren behind glass in Meshes, the one with which Durant begins his book, is so alluring, I think, precisely because it activates, among other drives, a subtle colonial fetishism for the Western viewer.) Alone in Haiti, however, Deren’s whiteness marked her as Other. At first, she could not accept this fact, and Durant includes revealing excerpts from her journals that put her thinking on display. When eventually she recognized the ethical impossibility of reconciling her subject position with the people of Haiti, she abandoned her Haitian film altogether — though she continued to study and practice the Vodou religion.

While Deren’s career flourished in the 1940s, her films ceased to generate the same level of buzz just a decade later. A growing preference for a looser, more improvisatory approach to artist filmmaking rendered Deren’s tightly orchestrated visions, and persona, as contrived. Though she defended her position with characteristic rigor, the blows reigned down. From today’s vantage, it is easy to see how blatant misogyny was taken up in what is essentially the tired refrain of Loosen up, Doll. For a particularly egregious example, see Durant’s chapter covering Amos Vogel’s 1953 Cinema 16 symposium on “Poetry and the Film.” Of the five panelists (Arthur Miller, Parker Tyler, Dylan Thomas, Willard Maas, and Maya Deren), Deren is marked not just as the only woman, but as the too-serious, too-studious overachiever. Onstage, she is publicly mocked and viciously heckled by her male counterparts for her intellectual analysis of narrative poetics, a theory later cemented by Roman Jakobson.

As the story too often goes with blazing women, Deren was ahead of her time for its majority, and then, in the blink of an eye, she was démodé, succeeded by Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke, Stan Vanderbeek, Peter Kubelka, Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, and Kenneth Anger, among others. Responding in The Village Voice to Mekas, whom she felt misunderstood her critique of his contemporaries as “amateur burglars,” Deren clarified that the word “amateur” was in fact the point of contention. “I am for the real bank robber,” she replied, “who gets down in the deep vaults.”

To “get down in the deep” could be Maya Deren’s mantra. She lived life at breakneck speed, and she loved with “a terrible sort of love,” as though nothing was louder than the tick-tock of mortality, “because this is my only chance to have the world […] [to have] that sense of the sheer fierceness of being in the world, the sheer and exhilarating violence of living.” To keep up with her desires, she came to rely on regular “cocktails” (as she referred to them) from Dr. Max Jacobson, the infamous East Village physician with a liberal outlook on amphetamine injections. After a session with Jacobson, Deren would stay up all night working on a film or an article, or “making detailed lists of the contents of her cabinets and closets.” She was in the habit of penning long, argumentative letters to her landlord, who had issued several complaints to her about the “strong odor of cats emanating from her apartment.” If the narcotics supplied to balance the speed didn’t work and she found herself awake at dawn, Deren would leash up her favorite cats for a walk in Washington Square Park.

There is more than a whiff of suspicious typecasting to the image of Deren later in her life. As a temperamental woman with five cats to my name, I find the persistent narrative surrounding Deren’s professional decline in early “middle-age” — ringed as it is with images of the spun-out matriarch, “Mother of American avant-garde film” but filially childless, shacked up with her third husband 17 years her junior and too many cats — disappointing, to say the least. As with Edie Beale in Grey Gardens, or the hoarders turned into public spectacle for A&E, the gendered cultural trope of the “Crazy Cat Lady” functions as a cipher for societal fears of aging; barren women are perverse deviations of the natural order who can therefore only be understood as weirdos or witches, cast out to the fringe with their animal familiars. I prefer to recognize in Deren’s fondness for cats a deep respect for alternative modes of communication beyond the scope of human conception — an openness and attentiveness to unbounded emotional consciousness. (Forever on the pulse, Deren’s 1947 film The Private Life of a Cat is a stellar precursor to the cute cat videos we gormlessly consume on Instagram.)

On the whole, Durant tactfully avoids pathologizing Deren (apart from reproducing the notion that her daily “frothing” and “inarticulate rage” over delays in her husband’s inheritance payout caused her to stroke). Likewise, his book doesn’t seek to overperform in the arena of critical analysis either (see the formidable volume Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, edited by Bill Nichols, for that). Instead, Durant presents us with key figures and experiences from Deren’s life, from which we might draw our own conclusions about her place in art and film history. I surface from this book with the blistering image of a woman who tenderly administered the brutal passage between sleep and waking, poetry and cinema, life and the performance of it.

Introducing her six completed films at a screening in March 1960, Deren concludes with the following words (they will in fact be her last public utterance):

I am not greedy. I do not seek to possess the major portion of your days. I am content if, on those rare occasions whose truth can be stated only by poetry, you will, perhaps, recall an image, even only the aura of my films.

When the house lights come up at the end of the show, the light in the theater is bright but diffused; it seems to come from all directions.

¤

Emma Kemp is a writer and faculty member at Otis College of Art and Design. She lives with her five cats in Los Angeles.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

All Hail the Guilty Pleasures: On Ali Liebegott’s “Rooms and Other Feelings”

Michelle Tea reflects on the paintings of artist and writer Ali Liebegott in the exhibition “Rooms and Other Feelings.”

Digging in the Dirt: On Jennifer West’s “Media Archaeology”

David Matorin reviews Jennifer West’s debut artist monograph, “Media Archaeology.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F01%2F8.-Cover.png)