Victim of His Own Celebrity: On Richard Schickel’s “The Famous Mr. Fairbanks”

By Chris YogerstAugust 7, 2022

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F08%2FFamous-Mr-Fairbanks.jpg)

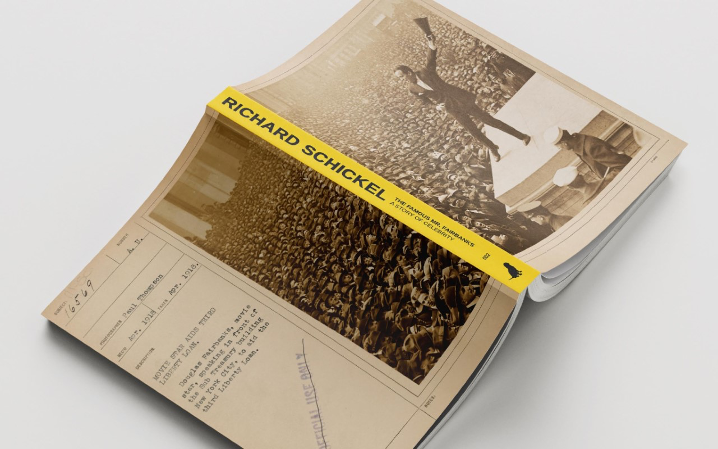

The Famous Mr. Fairbanks: A Story of Celebrity by Richard Schickel

Film historian Jeanine Basinger rightfully refers to this phenomenon as “an exuberant rise followed by an inevitable fall into a lonely confusion called celebrity.” In her introduction to Richard Schickel’s The Famous Mr. Fairbanks, Basinger applauds Schickel’s assessment of the always evolving culture of celebrity. “Critics are seldom historians,” she writes. “Historians define the past. Critics explain the present and tell us how we should think and feel about it.” This is a key distinction that often gets lost. There are always some critics who think they are historians, and some historians think they are also critics. The best, like Schickel (and Basinger), can operate on both fronts by historicizing while adding critical relevancy.

The famous “Pickfair” estate, a 22-room Beverly Hills mansion, soon rivaled the fame of its celebrity owners. Legends persist to this day of the stars who graced the now-razed residence. When Joan Crawford married Douglas Fairbanks Jr., the Hollywood legend told Basinger that “she wasn’t at first considered important enough to dip her manicured hands into one of Pickfair’s finger bowls.” An invitation to the famed residence was more highly cherished than a seat at a White House dinner. When Crawford was finally allowed entry, she was floored by the decadence, including “a twenty-piece orchestra, maids wearing ermine aprons, and someone to flush the toilet for you.” The fabled meals were a legend in themselves. Today at Musso & Frank on Hollywood Boulevard, you can dine on the coveted fettuccine alfredo whose recipe Douglas and Mary procured from a stubborn Italian chef after gifting him custom cutlery.

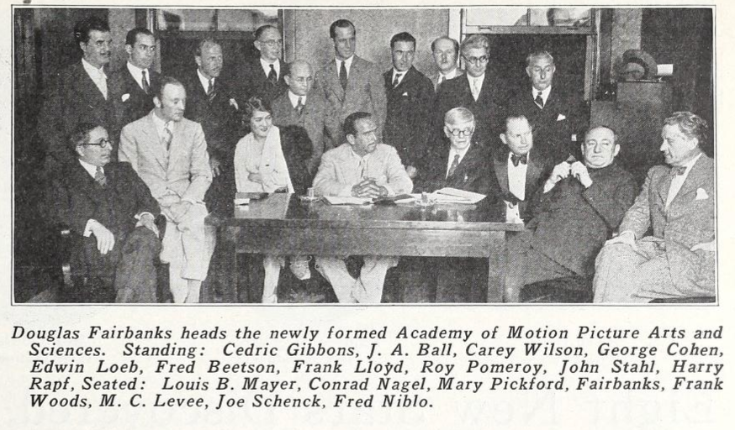

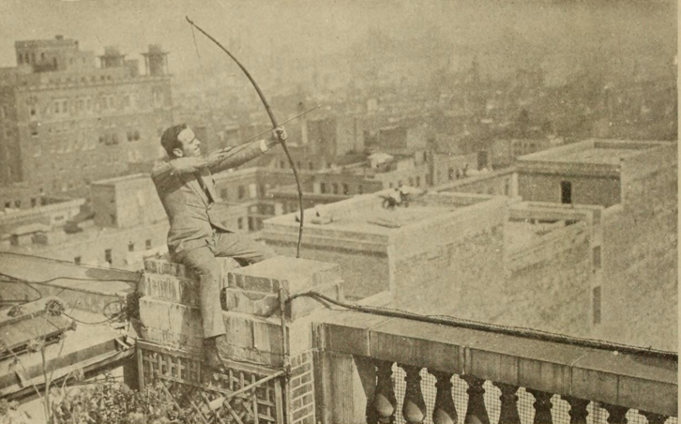

Douglas Fairbanks used his energy and confidence to become, in Schickel’s words, the “zeitgeist of America in the late 1920s.” For those unfamiliar with his career, Fairbanks was like the Tom Cruise of the era. He starred in many of the biggest action films and was always likable, yet when he played a villain, he did so to perfection. Fairbanks began his career in 1915 with Triangle Film Corporation, a company founded by Wisconsin natives Harry and Roy Aitken. Before he was done, he had worked with such celebrated directors as D. W. Griffith, Raoul Walsh, and Allan Dwan. A founding member of United Artists, the film school at USC, and the Motion Picture Academy, Fairbanks was referred to as the King of Hollywood. Films like The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), and The Thief of Bagdad (1924) helped create an unprecedented star image. Fairbanks also played himself in James Cruze’s lost metacommentary Hollywood (1923) and Show People (1928).

During the silent era, Fairbanks was at the height of his powers, but when synchronized sound came into play, his career suffered. The 1930s were rough: he separated from Pickford in 1933 following an affair with English model Lady Ashley (whom he would later marry). After spending most of the decade outside of films, Fairbanks suffered a fatal heart attack in 1939.

The Famous Mr. Fairbanks was originally published in 1974 as His Picture in the Papers: A Speculation on Celebrity in America Based on the Life of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. Schickel’s interest in the actor began when he was working on an essay for American Heritage in 1971. After reading the article, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. wrote Schickel a 20-page letter (included in this volume) offering extensive comments, context, and additional stories. Schickel had long been interested in the implications of celebrity, but the issue really came into focus for him when he read Daniel Boorstin’s The Image; or, What Happened to the American Dream (1961), later published as The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. Part of what Boorstin was getting at was the phenomenon of phony celebrity, of attention for attention’s sake. Yet the Golden Age of Hollywood was full of real celebrity — truly larger-than-life personalities and careers.

Schickel understands that there was a mix of talent and curated showmanship in a personality like Fairbanks. There was, of course, an element of the show-off in his performances, but it was (and still remains) deliciously palatable because he managed to communicate a feeling that he was as amazed and delighted as his audience by what that miraculous machine, his body, could accomplish. Effortlessly, he rescued fair maidens, humiliated and defeated evil villains, and escaped the enemy soldiery that fruitlessly pursued him, in different uniforms but with consistent clumsiness, through at least a half-dozen pictures.

Schickel waxes ecstatic about the ability of silent stars like Fairbanks, Keaton, and Chaplin to present themselves with such gallant spirit. Schickel’s enthusiasm makes clear that the silent era gave us a special gift — a kind of cinema that has never been duplicated and has lost none of its character. Schickel is aware that Fairbanks was modest about his artistic ability and saw himself as a fantasist. In fact, most celebrity was a fantastical creation. Mary Pickford, America’s Sweetheart, was in reality not a soft-spoken angel but instead, in Schickel’s words, “a tough, shrewd woman.”

In his analysis of silent cinema, Schickel builds on the work of preeminent film theorist Hugo Münsterberg, who asserted that film was more intimate than theater. On the stage, “the proscenium has a profoundly distancing effect — no close ups here.” Münsterberg’s infatuation with close-ups was central to his 1915 book The Photoplay: A Psychological Study.

Being famous for being famous was not the primary goal back then, as it is today in our social media–soaked culture. Prior to the invention of the Hollywood star system, celebrity was largely minimal. But the ballyhoo of Hollywood inadvertently paved the way for pseudo-celebrities to take over: reality TV stars and social media “influencers” who, as Boorstin predicted decades ago, would become “known for [their] well-knownness.” Of course, Hollywood’s first stars were not pseudo-celebrities; they were talented performers who were paid lavish salaries. Fairbanks and Pickford were among the first actors to have a great deal of control over their roles and contracts. This kind of power, according to Schickel, eventually led to actor salaries that pushed “production costs to uneconomic heights.” The top echelon of Hollywood included some of the wealthiest people in the world during the 1920s. Schickel muses on the impact of such an influx of riches that “bear no conceivable relationship to the actual value of an actor’s services.” Such wealthy paragons experienced “alienation from the ordinary masses, whose adulation must be mixed with a threatening envy, and who certainly cannot be expected to understand the problems of the overrewarded.”

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. had bittersweet memories of his father. “I always associated him with a pleasant, energetic, and agreeable ‘atmosphere’ about the house, to which I was somehow attached but which was not attached to me,” he writes to Schickel. “He also seemed to be someone I did not know very well.” Junior understood that the downfall of his father’s life and stardom was not his parent’s divorce; it was the shell of celebrity his father was reduced to — a journey through infidelity, drugs, and booze, and a search for identity. Fairbanks was “the first — but not the last — victim of his celebrity,” Schickel writes, “this force he had called into being, but which he, no more than anyone else who has undergone this most major of American transitions, could entirely or predictably direct.”

Schickel quotes the great sociologist Gustave Le Bon, author of The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895), who argued that “from the moment prestige is called into question, it ceases to be prestige. The gods and men who have kept their prestige for long have never tolerated discussion. For the crowd to admire, it must be kept at a distance.” The prescient observations of Le Bon at the end of the 19th century still resonate today. Consider the public downfalls of Kevin Spacey, Bill Cosby, O. J. Simpson. Even though their great achievements are still there, it is almost as if they didn’t happen. They’ve been erased from the popular imagination.

Like Boorstin, Schickel sees Hollywood-style celebrity arising in other circles of society. The Kennedy presidency, for example,

was maintained almost solely on the basis of a glamorous and enviable lifestyle — the movie-fan magazines took to covering the doings of the White House as if it were located in Beverly Hills — and perhaps destroyed by a psychopath enraged at the contrast between that life style and his own.

There were new rules in presidential politics: cave to the demands of celebrity or get left behind. The trend has been building for decades. Reagan was a Hollywood insider turned politician; Bill Clinton embraced MTV; Obama perfected a Kennedy-like swagger. Trump was a former reality television star and likely the first full-blown pseudo-celebrity president.

Schickel sees our obsession with fame as almost pathological:

It has been our pleasure, of late, to consider the entire movie business a has-been. That, too, is a form of compensatory punishment (and self-punishment). We allowed ourselves to care too much about it, to let it and its people and its legends mean too much to us, fill too many of the empty spaces in our time and minds.

Consider how social media users get wrapped up in every celebrity scandal, thumbing out half-baked hot takes by the second. Also consider the implications of elevating any politician to deity status. Schickel argues that celebrity soon became the primary product of Hollywood, with the art of film only a byproduct. We’re still feeling the ripple effects of that transformation today.

The Famous Mr. Fairbanks has been published by Felix Farmer Press, the brainchild of bestselling author Sam Wasson and producer Brandon Millan. (The press is named after the ill-fated producer-director in Blake Edwards’s classic 1981 satire of Hollywood, S.O.B.) As Wasson wrote in his introduction to their first release, Bruce Wagner’s novel The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories,

Between the popular trade book and the unpopular academic press, there remains an empty shelf in the Hollywood library. And as we do believe this empty shelf is representative of the blog-clogged “I feel …”–therefore-I-am personal opinions of TV-trained, identity-obsessed, anti-aesthetic appraisals of the Hollywood film, we are going to do our best, in love and rage, to fill it with Necessary Books.

Wasson and Millan understand that Hollywood history is dying. Film programs at major universities increasingly view the legacy of Hollywood with suspicion and condescension. The Motion Picture Academy Museum opened with minimal reference to Hollywood’s founders (many of whom were Jews, once again pushed to the sidelines). Wasson and Millan are taking upon themselves the responsibility of keeping great books about Hollywood in circulation.

In a conversation prior to the book’s release, Wasson told me that “while we watch Hollywood crumble today, it’s urgent to remind the world of how great Hollywood was.” He was enthusiastic to “endorse Schickel as a film historian”; most people know him as a critic for Time magazine, yet his work as a historian remains underestimated. Anyone who reads The Famous Mr. Fairbanks will quickly see how prophetic Schickel was, in addition to being a great writer. “Reading Schickel is like reading literature,” Wasson added, putting the critic on a pedestal with foundational film historians like Peter Bogdanovich, Jeanine Basinger, Joseph McBride, and Patrick McGilligan. After reading The Famous Mr. Fairbanks, I completely agree.

Millan noted that their cover images are meant to be “works of art” that speak for themselves without any overlaid wording. The spines are “author centric,” with the author’s name in larger print above the title (hat tip to Frank Capra). The Famous Mr. Fairbanks features a beautifully captured shot of the actor high above a massive crowd during a Liberty bond drive. This is the kind of cover you want to turn outwards on the shelf.

Felix Farmer publications are sold exclusively at Book Soup, unquestionably one of the best bookstores in Los Angeles. (Full disclosure: Book Soup has long been a supporter of my own work, as well as Wasson’s, so it’s only natural that they would get behind this drive to save Hollywood history.)

Millan told me that they are choosing books that end up becoming “part of us.” We’ve all had that experience after reading something truly profound. For me, one such book is Robert Sklar’s Movie-Made America (1975). The Famous Mr. Fairbanks is such a work, one that has only become more relevant with time, even though time had allowed this book to fall by the wayside. Until now.

¤

Chris Yogerst is associate professor of communication in the department of arts and humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His latest book, Hollywood Hates Hitler! Jew-Baiting, Anti-Nazism, and the Senate Investigation into Warmongering in Motion Pictures, was published by the University Press of Mississippi in 2020.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Man and His Persona: On “Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise”

A revealing biography of an iconic Hollywood star.

A Grim Purgatory: On Greg Jenner’s History of Celebrity

Aida Amoako considers celebrity through Greg Jenner’s history of fame, “Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!